People sometimes ask me, since I write about a noir circus underworld, whether my parents took me to the circus a lot. Actually, they didn’t. The main excuse was that all the hay and animals made my mother allergic, though it might also be that doing things with the kids never struck my father as a particularly good use of time.

People sometimes ask me, since I write about a noir circus underworld, whether my parents took me to the circus a lot. Actually, they didn’t. The main excuse was that all the hay and animals made my mother allergic, though it might also be that doing things with the kids never struck my father as a particularly good use of time.

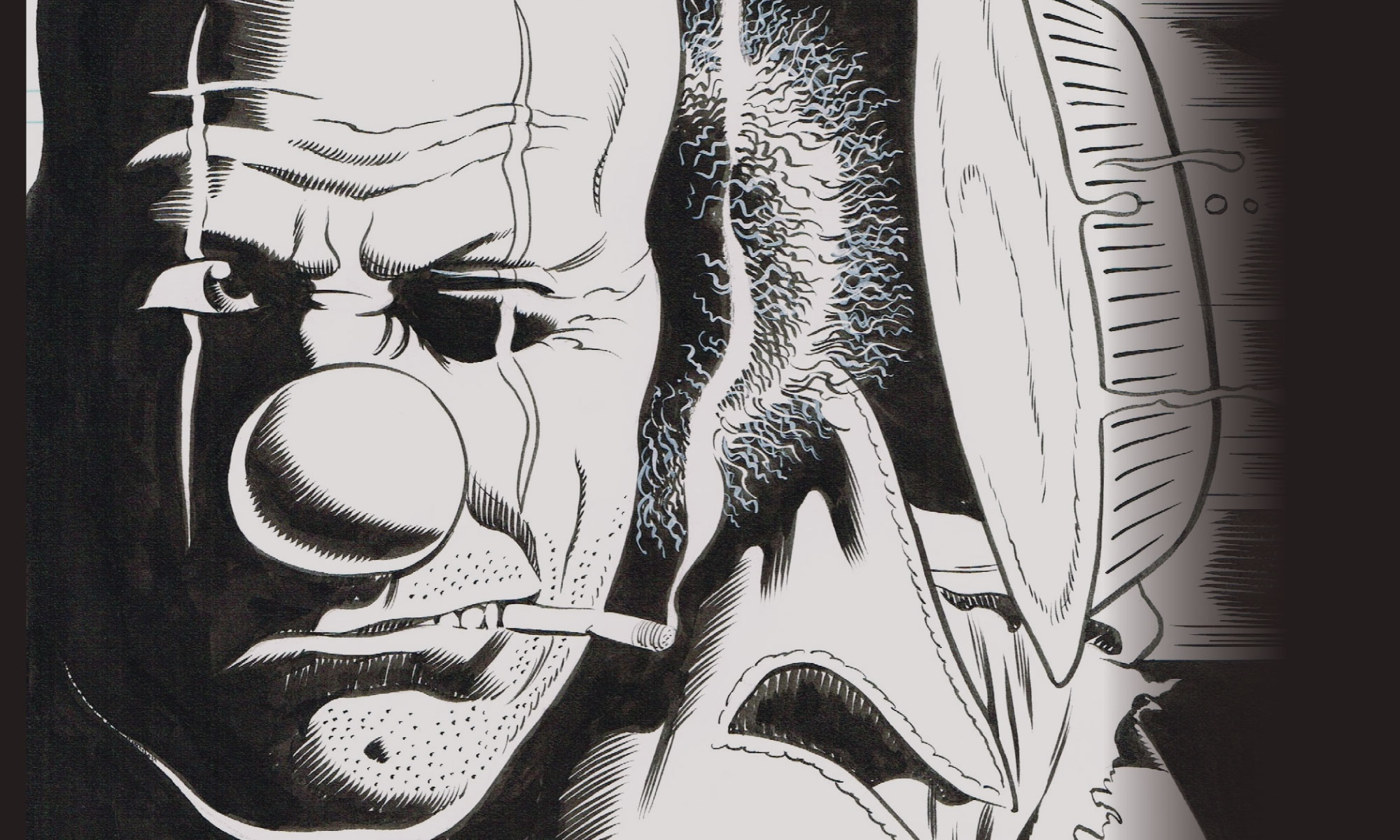

I don’t remember ever going to the circus, though I might have. My appreciation of it only grew when I began to research circus lore and practices for the “Rex Koko, Private Clown” books. One of the top perks of this research was taking my own kids and nephews to see live circuses, like the Big Apple Circus (on its one and only tour of the Midwest), the UniverSoul Circus, Cirque de Soleil, and of course, the old reliable, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey.

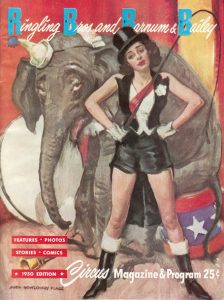

Like the seasons, Ringling came to Chicago with regularity, always at the end of November, forcing the Bulls and the Blackhawks to play on the road for two weeks. Tickets were pretty affordable. The crowds were always nice, though the arena was never more than half full. Many big Mexican families would attend, probably because circus still has a big legacy south of the border. I liked smaller circuses better, but Ringling brought that particular American value of “make it big, make it splashy.” I liked how they always tried to squeeze another buck out of us, as tradition requires. I liked it in much the same way I like opera: It’s people at the top of their profession, doing something strange and thrilling.

The news that Ringling Brothers would no longer tour hit me like a gut-punch last Saturday night. “Big Bertha” couldn’t end, could it? It had been going since 1870, since before Germany and Italy were nations. Since before professional baseball. Since before the Great Chicago Fire. For 146 years. And now, nothing.

I like circuses for the same reason I like parades: To reflect on how people are entertained. Beneath the high tech gimcracks of video and lights, the circus still exists because people want to see something extraordinary. A girl who can twist her body into shapes. Daredevils who like to walk on wires. Human cannonballs (how great is a human cannonball! Also something that premiered after Barnum & Bailey, in 1871).

And the animal acts. Protests against animal acts were what forced Ringling to shut down. When they “retired” their elephants from performing, their shrinking audience lost even more interest in attending. PETA can crow about it, and has been, of course. They’re zealots, in my mind, as unbending as abortion opponents. No middle ground, no grey areas. In much of the world, an elephant is a working animal, and only an idiot would harm a valuable animal that helps them make a living. Not denying there are lots of idiots in the world, of course.

I think the circus loses its appeal as its audience gets further away from the land, and further away from working with their hands. Only someone who climbs to fix a roof can grasp what it’s like to walk on a high wire. Only someone who knows horses can appreciate a really fine equestrian act. This is another part of the circus that tickles my imagination: What it must have been liked when it arrived in small, isolated towns. When locals saw an elephant for the first time, or a pretty acrobat in spandex. (Many young men also found other ways to enjoy women at the circus, though Ringling never had anything like that.) It was a venue of amazement, the Greatest Show on Earth. As someone said of Ringling, not admiringly, “The Biggest. The Grandest. The Goddamnedest.”

Now it’s gone. And no 3-D movie or virtual reality headset will ever replace the thrill.

Harry Lichtenbaum is an 86-year-old survivor of the Ringling Bros. Great Hartford Circus Fire of 1944. You can read an interview with him here.