At some time in 2006, my ISP lost a few months worth of my posts, and me, being the self-lacerating type, thought that the big gap in posting was entirely my doing. When I realized that I had actually been posting intermittently from May to September, it was too late, and the posts were gone for good. And probably, for the good of us all.

But I remember one post, because it was an essay that is still up on another site. Coudal Partners, a design and web firm in Chicago, had a project going called “Field-Tested Books,” in which writers penned small essays describing an indelible link between a certain book and a place. It’s a great project to poke around in, so go to the site and check it out. I was flattered to be included, and so I wrote about the connection I feel between my cottage and a certain collection:

A TREASURY OF DAMON RUNYON

Summer reading should be, by definition, that which Fall-Winter-Spring reading is not. And since my cold weather reading tends toward the current, the now, the wow-pow!, I set aside Summer to enjoy the things no one is talking about. At my family cottage I have a personal rule to read only books more than 50 years old. In this way, modern novelists and their narcissistic obsessions get the heave-ho, and I can enjoy stories from Twain, Dickens, London, Chesterton – hell, even Beowulf – that would otherwise get stacked in the pile of good intentions.

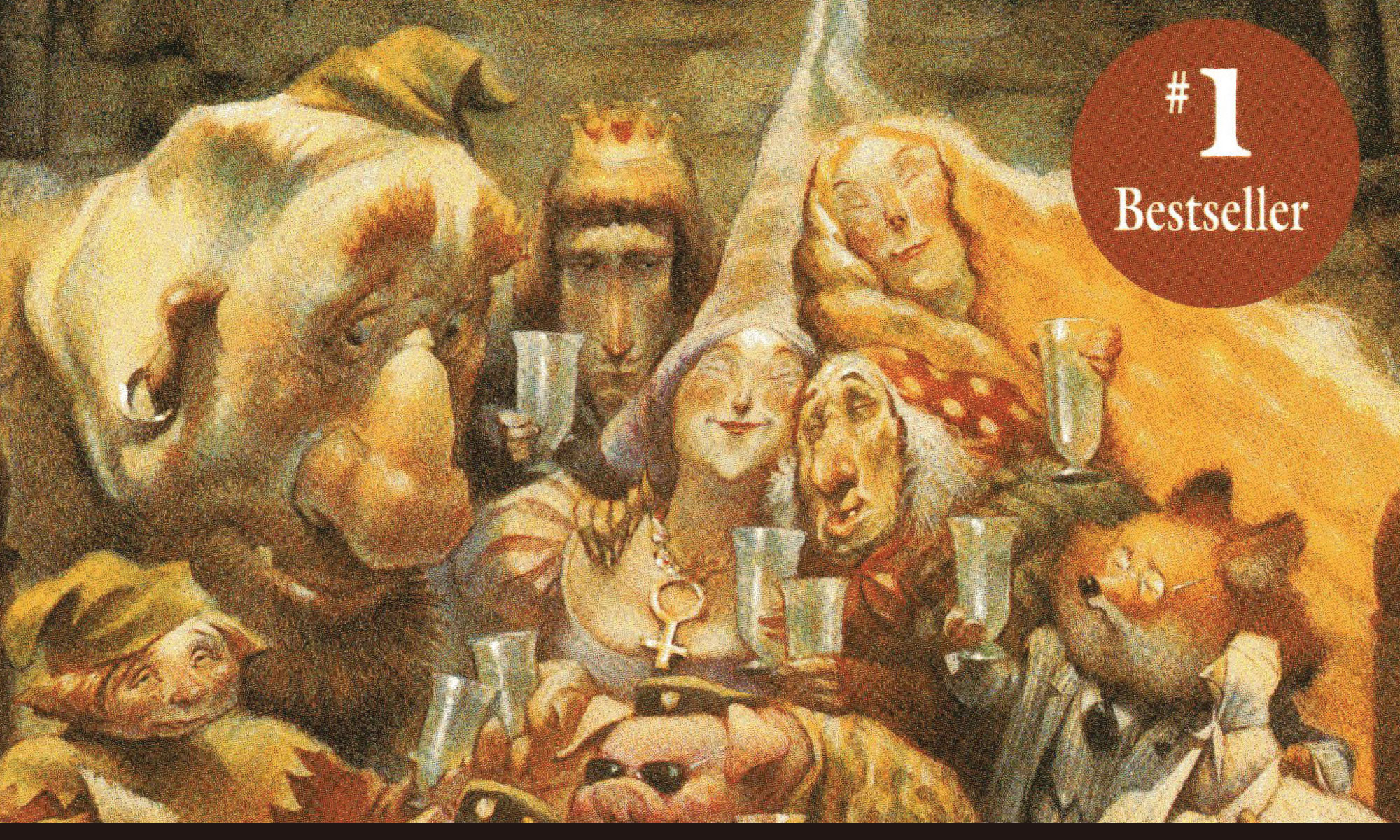

A couple of years ago at a book sale near the cottage, I found a copy of the Modern Library edition of Damon Runyon’s collected stories. If anyone remembers Runyon now, it’s because of Guys and Dolls, which adapted his yarns of mobsters, strippers, and tough eggs for the stage. His writing, I think, is a snapshot of style bordering on comic genius; at least there’s been no one like him before or since. Runyon writes strictly in the present tense, with no contractions and a cadence that sounds like feet scuttling hastily through a back exit. His narrative voice has influenced gangster-speak to the present day. Joe Pesci’s “I’m funny how?” speech in Goodfellas and the best dialog from The Sopranos would not exist without Runyon’s inspiration.

Runyon reportedly preferred his later, bucolic stories about small-town life in the Colorado of his youth, but these are tiresome “more than somewhat” when compared to tales of Harry the Horse, Blooch Bodinski and Nicely-Nicely Jones. The plots twist enough to please but not enough to vex, which is important in the evening after a glass or two of Canadian Club. These stories of thieves, grifters and racketeers carry a special tonic for a visitor in this part of Michigan, which was settled by Dutch Calvinists whose idea of a good time is a hard day’s work. Like P.G. Wodehouse’s, Runyon’s stories feel like a blip in time, profiles of a moment that had passed by the time they were first published, if it ever existed at all. If summer days can be well spent relaxing in the shade with Bertie Wooster and his Aunt Agatha, then the nights belong to the idle denizens of Mindy’s Restaurant, the Golden Slipper Nightclub, and “the racetrack at Saratoga, which is a spot in New York state very pleasant to behold.”